I’m in the process of planning and interpreting the cultural probes for the first part of the study in thinking of ways to work with people in a visual and material way. So two things happening – first thing is trying to think about how I work with people to get to know them as the first points of reference and the points of departure. So for this, I’m looking more specifically how the cultural probe has been used in the past, as a provacative tool, to prompt a de-familiarisation of self and the habitual, to enable a process of stepping back and considering what, who and which aspects of your life are considered important. As part of this, there are the cultural references which we draw from. But part of this is thinking about the fact I can’t assume everybody has the same cultural reference points and points of departure. And this is where I am having difficulty at the moment, since I have to almost imagine what those cultural reference points might be until I get on and meet people. I think what I have so far is pretty safe, using maps to signify obvious spatial connections, using a phone line for points of connection, cinema film strip for the film of your life for points of transformation and change, motivating factors, hills and valleys of the high and lows. I need to think more carefully how I might package all of these things as points of departure. I’d thought initially that this would be good packaged as a suitcase, but this might be too much. I’m not sure the suitcase is too literal for this process. And if it is a suitcase, what kind is the most appropriate physical thing? This might be too obvious and I’m not sure of the materiality of such an object. I’m making a case for the idea of mobility, but is mobility always about the packing of things and leaving of things. What we choose to take in our heads and our hearts, and what we choose to take physically as things. Mobility is often just as much about the mental shift, which occurs through accumulated experience over time. This can happen without physical shifts across geography. Are there mental shifts which occur anyway when we realise something about who we are or what we can’t have or what we can’t be?

Going back to the idea of the suitcase, it does make sense for there to be some sort of a package or kit to keep all these items in.

Part of this is also understanding aspects of the vocabulary that people use and I am using within the research. There is the research language that I am assigning to the work, aspiration, migrant, mobility. I’m wrestling with this vocabulary which changes as I am writing the participant and partner information. Partly this is due to the connotations that words such as migrant, aspiration have and where they exist in people’s vocabulary and perception. Will the people who will be involved in the research, see themselves as migrants. When do you stop becoming a migrant? It was funny the other day when I announced my PhD research title across the table to one of the others in the lab, who questioned what that actually meant. When talking to another researcher he said could you change the word aspiration to hope or dream. I can see the that. For me they all have different connotations. Aspiration, for me is particularly loaded. It has become synonymous with a sense of ambition and forward thinking linked to education and achievement and assigned to regeneration and New Labour. Etymologically the word has two roots, one about breathing the other about goals

- aspiration (1)

- 1530s, “action of breathing into,” from L. aspirationem (nom. aspiratio), noun of action from pp. stem of aspirare (see aspire). Meaning “steadfast longing for a higher goal, earnest desire for something above one” is recorded from c.1600 (sometimes collectively, as aspirations).

- aspire

- mid-15c., from O.Fr. aspirer “aspire to, inspire” (12c.), from L. aspirare “to breathe upon, to breathe,” also, in transf. senses, “to be favorable to, assist; to climb up to, to endeavor to obtain, to reach to, to seek to reach; infuse,” from ad- “to” (see ad-) + spirare “to breathe” (see spirit). The notion is of “panting with desire,” or perhaps of rising smoke. Related: Aspired; aspiring.

- This second one is really interesting, with the link to spirits of rising smoke and infusion. Interesting to see how the word has very early roots in Medieval Europe, with a Latin derivative. When I knew it had two meanings, I thought this was a little random, but it seems the root links breath with something we wish to obtain. It might be worth thinking more about this, and doing some more research, or at least maybe asking an etymologist of some description.

- This links very well with the discussion I was having with another researcher, about the nature of aspiration and how it fits within HCI, and more specifically within experience-centred design and Wright & McCarthy’s discussion of the holistic self, which we often seek to understand when working with people. Ideas around aspiration of how we articulate hopes, dreams and future selves is seldom written about. I have found a few references to these aspects, but in HCI there isn’t much attention paid to this space and yet it plays a really important part in any design space, since we are always designing for a future. When John McCarthy came a few weeks ago and we met for the first time to talk about the PhD, he talked about the possible relationship between nostalgia and aspiration. I had been thinking about aspiration as in a different imaginary space, somewhere out there to be grabbed and made, but John spoke about how we make the future from what we already know too. There is an interesting space between Lucy Suchman’s plans, how we articulate the plan, how we might visualise what we want to happen, in a design context and then how that might pan out in reality. What she writes is way more profound than that, and so I probably need to go back and look at exactly what she says, but there is a certain sense of aspects of the plan being worked out as you get there, as you meet the challenge and finding it different to what was anticipated. She uses the analogy of the Trukese and European sea navigators, the former having an objective and the latter having a plan. She suggests these two analogies map different views of human intelligence, the European which is founded on repeatable and purposeful action, the latter ‘contingent on unique circumstances’ (Human-Machine Reconfigurations p25). I’m not going to get into this right now, but there is something interesting in what she says in relation to the plan in relation to ideas of aspiration and notions of ad-hoc and embodied knowledge. I haven’t read all of the book yet, but I wonder whether there are some issues with the polarity of articulating the Turkese as more in tune to work with what happens in situ, in the natural environment and the European reliance on the plan.

- There was an interesting conversation with Pete too about when you’re a kid, you want to be something fantastical, like an astronaut or a dancer. I was thinking about this, and maybe the practical side of me meant, my first sense of what I wanted to be was a nurse, like my cousin Liz. I was about four at the time and mimicked some of the things I expected her to do. I had a small toy plastic hammer, which I tapped on people’s knees as I crawled across the floor of my nana’s orange kitchen. Then I wanted to be fashion designer, then an accountant, a journalist, then a costume designer. And these decisions changed all the time. There was a sense when I was 12, of just wanting to go to university, partly as I knew I could escape. I read and wrote quotes on the wall so I could wake up with the words that would help me become clever enough to get to university. There was also an internal family compulsion to go to art school and get a good education, where my grandfather had been. My mum and dad didn’t push for me to do anything, I was always awkward and did what I thought was best.

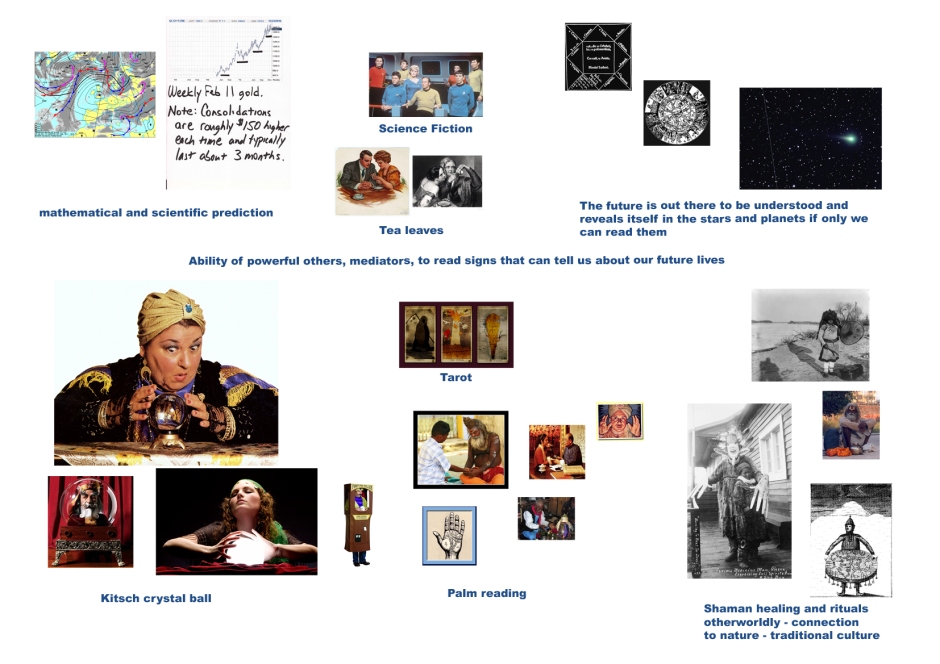

- In thinking more visually about how we might plan and think about the future, I remembered when I was a teenager I was obsessed with going to see fortune tellers, tarot and palm reading. On reflection, it was probably a way of abdicating responsibility on how to make decisions about the future, hoping in a sense, it was already written somewhere and I could just go out and get it and work towards it. Like reading horoscopes, I had to read them in order to see what might happen, so I was ready to spot the opportunity. So this is me drawing together these different ideas around future visioning and how people have done this over time. There is a certain exoticism about the imagery, which is quite interesting. The shaman images are interesting too. I’ve chosen these because of their colonial overtones, but also I find them really intriguing in the way in which the camera frames them. They remind me of the kinds of spiritual photographs of the C19th and the otherworldlyness of the shaman character, not quite human, partly animal. It reminds me of the Michael Taussig work on mimesis and alterity and the performance work of Marcus Coates. It also reminds me of the paper, that Susan Wyche has written about the pentecostals in Brazil and the positive and negative spirituality imbued in the technology. This isn’t all worked through yet, but I’m really excited about some of the connections.